Generation Rooftopping

Table of Contents

1 Urban Exploration as a Lifestyle and Leisure Activity

2 The Case of Rooftopping in Frankfurt

3 The Dangers of Rooftopping

1 Urban Exploring in the world

Rooftopping became a global trend in 2011. However, the vertically built city type we know from modern days has existed for already 100 years. What has changed since the first cities rose high to the sky and progressively became shaped by skyscrapers? After the pyramids were built 5000 years ago, the idea of climbing to their tips probably wasn’t a good one at all. In the 11th century, in the tower villages in Tuscany, Italy (see fig. 1), I assume no uninvited foreigners intruded upon these private power symbols to enjoy the panorama. But since the industrial revolution, economic wealth has been on the way to making human resources superfluous: Technological modernization is providing a growing number of humankind – not only the elites - with time and opportunities to reorganize their lives relatively free from the pressure of elementary economic reproduction and to seek further goals and meanings.

Also, relatively recently in the overall history of mankind, urbanization created a totally new kind of environment. Economic progress - expressed through a sheer boom of physical constructions - led to the emergence of massive buildings, bridges, paved streets, and other urban infrastructure. In the 19th century, roof climbing became a secret fad among students in the UK. They climbed on the cathedrals and gothic buildings of Oxford and Cambridge after dark. At this point, The Night Climbers of Cambridge (1937) has to be mentioned, a photo-book with the self-portraits of early rooftoppers.

It is said curiosity is a genetic inclination of all cognitive species.

In the modern West: With big cities always came explorers, people who are curious about their not so obvious surrounding. The urban explorers of New York, London and Los Angeles explored tunnels, sewers, bridges and abandoned factories since decades. They kept their actions concealed from the public eye, as they preferred the cover of night. However, evidence of their expeditions is scattered across various urban landscapes: letters scratched into the sandstone of old bell towers, marker tags on bridge pylons, and layers of graffiti in subway tunnels. There are self-published DVDs and photo-books featuring people’s interest in tunnels and deserted structures, with titles like The Space Between (2008) by John Law or Snowshoeing Through Sewers (1994) by Michael Aaron Rockland. Even in Germany, where concepts like urban exploring were unfamiliar just two decades ago, one can find names and dates scratched into the old towers of Cologne Cathedral, serving as documents of more than a century of exploration spirit.

Despite this shared curiosity and a penchant for the vastness of unexplored spaces, exploration has evolved into distinct forms, transcending thoughtless spontaneous ventures typically associated with young individuals. Explorers now identify with specific categories such as urban exploring, lattice climbing, or subterranean exploration. Soon, digital photo-cameras have made it into our lives.

The foundations of today’s Rooftopping trend have been set by small, informal groups of professional and semiprofessional photographers, who focused on visually documenting the cityscape. At this point, the evolution of rooftopping might be explained due to a photographer’s dilemma: To be a photographer in a city means to look for motives in one’s urban environment. To conventionally photograph the cityscape, I simply have to purchase a ticket for an elevated observation deck. But the closing time is usually 8 pm – what a pity, if I prefer taking photos at night. Normally, written requests to the management are ignored or declined. To solve this problem, the interested photographer decides to climb the scaffolds of a construction site, which promise a good view, a quiet place to concentrate on the right composition, and a yet rarely seen perspective. This behavior collides with the omnipresent safety syndrome in today's society: anxiety of insurance, anxiety of terror, anxiety to lose one's image etc. – a time in which such things are forbidden in fact and principle.

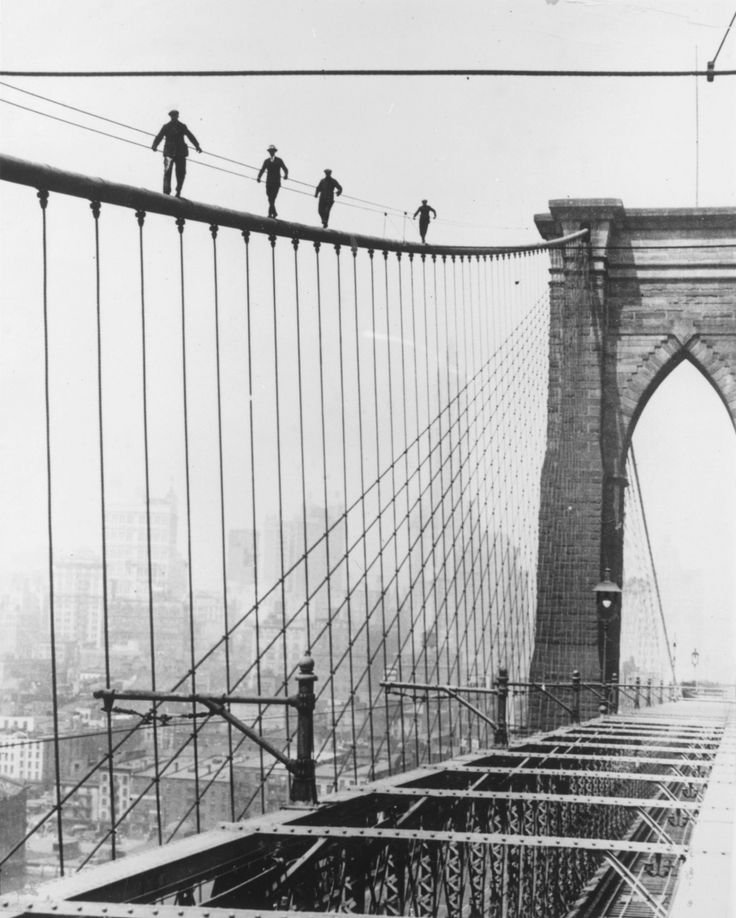

iIn the early 20th century, American cities underwent a dramatic transformation driven by a peaking industrial growth. In 1920s New York, Manhattan stood at the forefront of this progress, marked by architectural innovations, Art Deco towers and intricate ornamental designs that defined the new skyline. Manhattan's skyline was transformed by iconic high-rises, and this rapid urban change became a focal point for many photographers. Photojournalists like Margaret Bourke-White, Charles Clyde Ebbets, Tom Kelley, William Leftwich, Eugene de Salignac, and Lewis Hine not only documented these transformations, but also used the newly built Art Deco towers to capture sweeping views from their rooftops. But rooftopping did not only take advantage from the new vertical architecture.

Fig. 1: A historic etching of 12th century Bologna, taken from A. Finelli’s Bologna ai tempi che vi soggiorno Dante, 1928.

Rooftopping is a new phenomenon closely related to the rise of social media.

What characterizes today’s rooftopping trend is the purposeful use of social media. Here the rooftopper presents one’s newest achievements, activity and photographs. Doing so, they join an implicit contest. Due to the relatively high costs and efforts in the beginning of this century, internet technologies were used only by "professionals". In 2005 Flickr became world’s first photo platform in the web. It was also the first social media means for of small number of rooftopper sat that time.

Gradually, while prices for digital cameras and computers dropped the internet became ready for the masses. Since 2011 smartphones with permanent mobile internet access are in everyone’s pockets.

In the Western hemisphere, Mr. Rooftopper from Toronto is known to be the first rooftopper to receive viral recognition in 2011. At this time the internet was already full of cell-phone videos from Russia: Bawling teenagers on colorless apartment blocks, rope swings below bridges, circuslike balance action on cranes. Here, the illegal climbing of roofs had developed into a prominent subculture for the Post-Soviet youth, which grew up in a (social) context quite incomparable to our own. Also in 2010/2011 photographically excellent images were coming from there.

The “Model of the evolution of a trend” can be consulted to scrutinize the rise of rooftopping. The model emphasizes certain development stages of popular leisure culture in the postindustrial era.

1. Invention: New psychological motives and technical alternations are recombined with already existing "spaces of action" – i.e. the roof - by pioneers.

2. Innovation: The rooftopper become developers and are influencing/shaping the art of rooftopping themselves. Sometimes it takes several "generations" until the movement attracts a larger group of practitioners.

3. Trend: In case the cultural setting and the nature of rooftopping, match "rooftopping" is about to become a consumable good and get commercialized.

4. Over saturation: In case sensational moments and sensational photos fray after some time.

As mentioned in this concept, there are different generations of rooftopper during the various phases of the phenomena. While the cultural media is about to soak up the trend, for example, the original pioneers and inventors remain in very different mood due to their very different intentions and experiences. This drives a conflict of generations. Depending on the social environment, rooftopping can remain in any stage for a certain time. But it may easily expand into a touristic fad – Hong Kong and Dubai are examples of popular destinations of rooftopping tourism in the 2010s.

In Western Europe the trend took a foothold in UK, France, Germany and Italy.

Noticing how similar in practice, rooftopping actually developed in the different metropolises was very interesting to me. It appears almost like the copy of a unique trajectory, multiplied in time and space.

Each city behaved like a closed, independent system where rooftopping needs to be reinvented, individually.

And I asked myself: What do these peculiarities say about the societies we are part of?

Fig. 2: Silhouette of a young male enjoying the sunset on a rooftop in Frankfurt's financial district.

Fig. 3: Ancient tags — names carved in the stone of Viennas tallest bell tower. Similar tags exist all over the world, whether it is on the top stones of the Pyramids of Giza, inside the North tower of Cologne’s Cathedral, in the service rooms atop Chicago’s and New York’s first generation of high rises, or on the derelict radio antennas in Elektrostal, Russia.

2 The Case of Rooftopping in Frankfurt

Frankfurt is not New York, of course. But urban explorers were born here, too. It is difficult to say how many, because they used to do their things mostly undercover. For me, it is cheering to trace back this spirit.

6 years ago, I talked to an acquainted schoolmate. By coincidence, it turned out he has been on the crane of then already demolished Henninger Turm - which was a gigantic abandoned grain tower of 120 meters height. The local explorers in Frankfurt never developed into something that could be called "a scene". They were more referred to a handful of isolated, small groups of friends who just did "their thing". Very much like other teenagers coming together for a barbeque on a sunny afternoon. A real name for their activities as well as an interest from the outside didn’t really exist. The brewery relict Henninger Turm, an abandoned office building at the Eschersheimer Landstraße and a vacant university tower had been the objects of interest of the curious youth for years. The local Parkour people simply called their nightly climbing activities on multilevel car parks and other building sites a "roof mission". The first meetings with officials were relaxed. On the roofs, window cleaners allowed us to stay for a while. Police went for some small talk down the crane at 2 am. But of course: every meeting in which those parties were involved meant two steps closer to trouble.

In Frankfurt, a city of 730,000 habitants, it took about seven years to really heat up the conflict with this new subcultural activity.

In the following, I summarize the major events during the first years of rooftopping trend in Frankfurt. The purpose is to provide a concrete example for the rise of a new urban leisure activity, and for documentary reasons:

2000s: Exploring the urban landscape was part of some sub-cultures like Graffiti and Freerunning. In 2012/2013 Frankfurt’s Parkour and Freerunning community was in full bloom. And in a couple of videos, that were occasionally put on Youtube, the on-top-aspect was paid special attention.

2014: The beginning of viral rooftopping videos: Up to five people filmed themselves climbing construction sites and hotel buildings for the purpose of presenting it on YouTube. Another very small number of people used Instagram for their photos.

2015: Rooftopping’s very first newscast appearance in the Bild Zeitung, a big German tabloid newspaper, about a masked rooftopper; some online blog articles from two rooftopper from the Parkour and Freerunning scene followed immediately afterwards.

2017: The number of people calling themselves Roofers steadily grew, slowly the encounters with police in the end of 2017, too. With a little delay, the trend raised in the other German cities. In comparison to most other big European cities, Frankfurt is one of a few high-rise meccas and became interest for foreign rooftopper, as well.

2018: Two young rooftopper couldn’t resist going to the medias: this public pop up and actively harassing propositions about the lack of safety in major banking and insurance headquarters raised the attention of the police. The public attorney of this time directed a police commission to execute a search warrant for two rooftoppers to stop the trend in the core. But on the long, this didn’t work out.

In the other cities the story goes the same: the official narrative of "a safe city" gets undermined by the rooftoppers – who can enter office towers, private property and critical infrastructure just for fun. To give an outlook on further happenings Frankfurt is going to be faced with it can be derived from the cities, e.g. London or New York, that are some steps ahead.

1. New generations of rooftopper will follow.

2. Their actions will become more extreme, dangerous and from today's point of view even more "senseless".

3. As long as the rooftopper don’t get caught in flagrante delicto, legal proceedings are unlikely.

4. Property owners have to take charge themselves: Making their roofs inaccessible and boost the head count.

Fig. 4: "Lunch atop a Skyscraper" (1932) by Charles Clyde Ebbets, Tom Kelley, or William Leftwich, published in the New York Herald-Tribune, Oct. 2 1932.

Fig. 5: "Brooklyn Bridge showing painters on suspenders" (1914) by Eugene de Salignac, Municipal Archives of the City of New York.

Fig. 6: "Four men climbing Brooklyn Bridge in New York City as part of a test for applicants wishing to be appointed to paint the bridge" (1914) by Unknown, Topical Press Agency.

Fig. 7: “Margaret Bourke-White atop the Chrysler Building” by Oscar Graubner. Bourke-White, a renowned photojournalist, known for her documentary and aerial photography, had her studio on the 61st floor of the Chrysler Building, right beneath the gargoyle from which she regularly took photographs.

Fig. 8, 9: Behind the scenes of photographer Charles Ebbets capturing daring perspectives (Fig. 8) and a worker posing for the camera (Fig. 9) during the construction of Rockefeller Center in the early 1930s.

Fig. 10: Fashion photographer Erwin Blumenfeld captured the model (Lisa Fonssagrives) on a steel beam of the Eiffel Tower in Paris, published in Vogue, 1939.

Fig. 11: "Shadow Climbers" (1950) by John Bulmer, published in LIFE Magazine. Roof climbing as an initiation rite for student societies.

Fig. 12: "Man smoking on the Pyramid of Giza" (1981) by Louie Psihoyos.

Fig. 13: Likely taken around 2008, this photograph of two workers sitting on the bell of Mecca’s Royal Clock Tower began circulating online in 2014. While the photographer remains unknown, the image marks a pivotal moment in the evolution of photography and its digital turn.

3 The Dangers of Rooftopping

“Lunch atop a Skyscraper” a staged photo taken in 1932 [see Fig. 4] became one of the most famous black and white pictures, ever. The photo was reproduced uncountable times and hung in many living rooms – without indignant judgment. Opposite to this, society’s view on rooftopping today is very polarized: Some can understand, others absolutely don’t.

In the past years, the tabloids equivocally branded rooftopping "a dumb activity inspired by Russian idiots". Commonsense disapproves to this hobby because it is "life- threatening" and "illegal".

Stigmatization is a useful tool to intervene in urban-social dynamics and to undermine dangerous developments. In the social fabric, the tabloids are in the proper position to do exactly this. It also works by the means of social control – a core statement of the critical media theory.

This urban activity is not only physically dangerous for the actors, it is also dangerous for the social order: The internalized moral/lawful conceptions are in jeopardy due to the dissidents’ inner fascinations, subdued feelings or an aroused different purpose of life.

But the problem is: with YouTube, Instagram and Co the young generation has its own media. And they are using it extensively. In 2018, various surveys indicated: the average German teenager (15-25 years old) spends around 200 minutes on the Internet daily. The influence of likes, views, commentaries etc. – the system of online social participation and evaluation – on the human psyche should not be underestimated.

Proudly presented rooftopping content can get millions of views. On the roofs video "Shanghai Tower" from 2014 was the first big breakthrough - today (2019) it displays 75 millions views.

Rooftopping has the potential to delight society’s younger generations: The pictures that could be taken, the adventures could be made, the thrill could be felt, the stories could be told, are totally fascinating: these are desires and experiences definitely not part of today’s offers for a mainstream lifestyle.

In Russia, roofing became a national sport that also caused many hundred dead victims. Without pushing this singularity too far, but it’s worth an exemplarily warning.

In this digital space, the leeway of most authorities ends.

In the digital space, too, Rooftopping encountered the lure of commercialization and provoked new restrictions.

Popular photography and clothing brands like Canon, GoPro, Converse, Nike, Red Bull have begun 2015 to use the viral trend for marketing their products. The advertisement clips – which were only shown on the Internet - featured well-known roofing-athletes (e.g. On the Roofs, Daniel Lau, Oleg Cricket, James Kingston). It was in 2016, I can very much remember, when a billboard advertisement at a train station in Frankfurt caught my attention. The billboard depicted female legs dangling high above the street. It was an advertisement for GoPro.

A general observation: In 2016 the number of TV advertisements showing young people enjoying life on rooftops, multiplied.

With YouTube rooftopper are able to earn money by displaying ads in their videos: around 1,000 US $ are paid per 1 million clicks. In western countries the first successful "professional" rooftopping-vloggers (with >1 million subscribers) were made in London. Their names were Nightscape and Ally Law.

By the end of 2018 YouTube has made a step back: It restricted the roof-vloggers and other extreme-sportsmen to monetize their videos. YouTube began to set age limits (+18) to the videos. Apparently, the Silicon Valley giant struggled with moral reproaches. To avoid bad talk, YouTube set up new policy rules and upload filters - a step by which not only the rooftopper lost a possibility to gain money but also the video-platform itself. Today in 2018 most rooftopping activities (in western societies) have shifted towards Instagram. But there the possibilities for earning money are more difficult because Instagram does not pay out money directly like Youtube did.

While in Russia since the start of roofing many hundred people plunged into their deaths and the recent death of the Chinese rooftopper Wu Yongning in 2017 the number of rooftopping victims in Western countries do not count high digits. For the US, two fatal accidents can be researched: 2017 a 24 years old man in New York; 2012 a 23 years old man in Chicago died while taking photos on the roof.

At this point, the dimension of "rooftopping victims" has to be considered: Imitators and performance pressure are inherent parts of extreme sports themselves. Access to the top of an average house can be physically really easy. What if an inexperienced person emulates walking around on a roof?

In 2018 two 16 years old girls thought it would be safe to step on the glass roof of the University of Applied Science in Frankfurt. Both broke through it. One of them broke her spine. In 2012, I knew of another girl who broke through a plastic hatch and landed in the floor below.

Definitely inspired by rooftopping was the 13 years old boy in Frankfurt who slipped off an old harbor crane in 2017. He got seriously injured while he and his friend were taking photos and videos on the crane at night. Other, deadly, incidents happened when alcohol came into play: a 23 years old man was found dead below an abandoned office building in 2014. Alcohol always mutes sanity in people. A sanity that was missed in all these accidents is the natural, healthy respect of heights that holds one on distance to the edge. Mistaken confidence makes people lose the awareness for their potentially deadly position.

The withering of specific human instincts is normality in the era of consumption societies. To oblige, natural behavioral instincts become "old school" when living in the urban environment.

Rooftopping is not only a phenomenon of the vertical city, it is a phenomenon originating in the very heart of today’s system of perpetual consumption.

Metropolises as living spaces are very strictly administered realms. Paternalistic laws, public surveillance, and smart infrastructures intend to ease people’s way of living. To function smoothly, big cities only allow a restricted level of individuality. Up to a certain degree, people adapt to these limiting circumstances by themselves. Working routines, pseudo individualized choices of mass products and financial restrictions are providing multiple guidelines for lifestyles by default.

Cities want to offer a good quality of life for their citizen: dwell along the river bank, green areas, fresh air and recreation areas. But actually in many modern cities the latitude for their citizens decreases. Deft marketing strategies were able to make even this attractive: Since 2016 the very successful gym chains – at least in Europe - sell the most popular and most monotonous new urban leisure activity to young people. This stays in contrast with a rich-of-hormone-distribution activity like rooftopping.

On the other hand, the way rooftopping is often practiced couldn’t reject the influence of the omnipresent consumer culture. Spending time on rooftops is turned in an entertainment product, regularly consumed without sustainability and consideration for third parties, grazed and dropped down. In theory, the urban exploring scene follows the rule "take nothing but photos, leave nothing but footprints". This virtue does not refer to the motives of the later born rooftopping-trend: The goal to stay below the radar gets challenged by improving video surveillance, alarm systems and security guards. To overcome them, the rooftopper are willed to trigger them, be faster and leave before the security personnel can grab them.

Media and society are regularly blaming the rooftoppers for behaving "attention seeking".

But on the other hand, recently many rooftoppers tend to focus more on their "real-life-experience" and sometimes they also leave their cameras at home. This change in the rooftopper's perspective is tightly intertwined with a second trend wave reaching young sensation seekers (also without a camera). In Europe, I observed this happening in 2018/2019.

While authorities see the fans of roof-vloggers in danger of becoming addicts to rooftopping themselves, I can calm them down. The Netflix-and-chill-mentality already has blazed its trails: "Everytime I watch this guy's videos my hands sweat". Rooftoppers don’t watch v-logs, they rooftop, ‘til they get bored.

- January 2019

Fig. 10: “MY FFM”, a private photo collection, showcasing early rooftopping photographs from Frankfurt am Main (2014–2017).